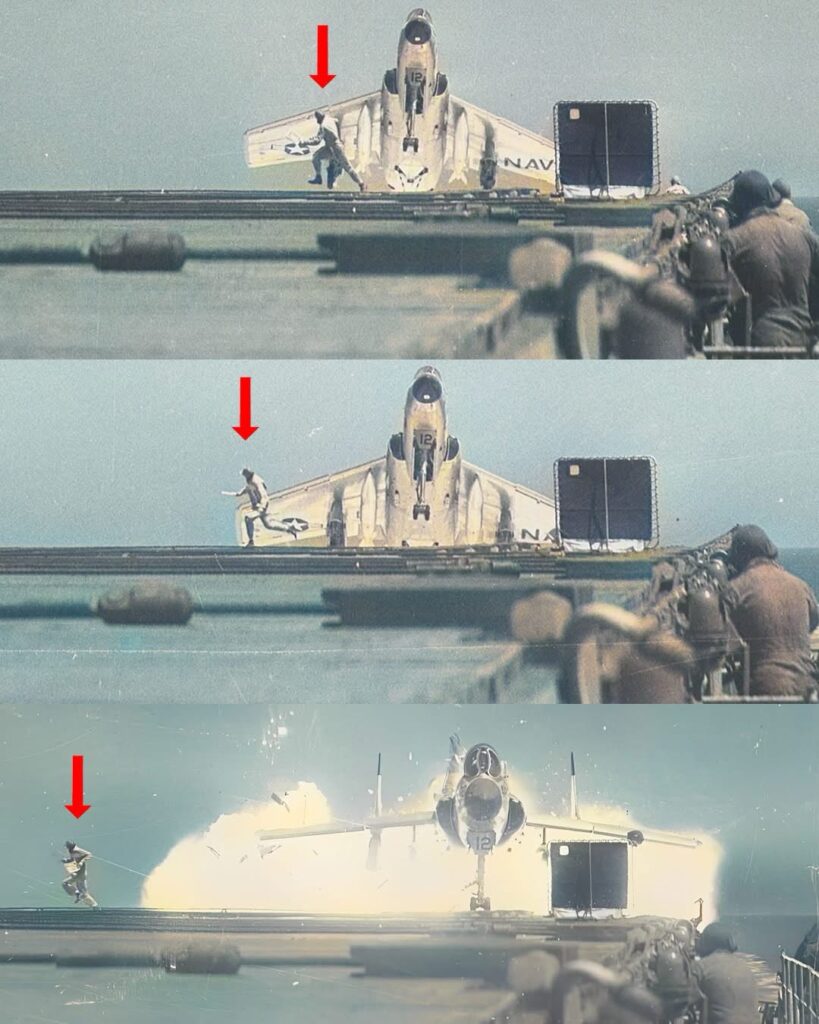

A dramatic and haunting photograph shows the infamous Vought F7U-3 Cutlass moments after it crashed violently onto the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hancock (CVA-19). The image freezes a split second of Cold War naval aviation history—twisted metal, scattered debris, and stunned deck crew standing amid the chaos. More than just a shocking visual, the photograph symbolizes the troubled legacy of one of the U.S. Navy’s most controversial jet fighters.

The Vought F7U Cutlass was a radical aircraft when it first appeared in the early 1950s. Designed without a traditional tail and featuring sharply swept wings, the Cutlass looked futuristic, almost experimental. At a time when jet aviation was evolving rapidly, the U.S. Navy hoped the Cutlass would give it an edge in speed and performance over potential adversaries. On paper, the aircraft promised innovation. In practice, it became notorious for its dangerous handling characteristics and alarming accident rate.

The crash aboard USS Hancock occurred during routine carrier flight operations, one of the most demanding environments any aircraft can face. Carrier landings require precise control, instant throttle response, and structural durability. Unfortunately, the F7U-3 Cutlass was ill-suited for such unforgiving conditions. Powered by underperforming engines and burdened by a high landing speed, the aircraft gave pilots little margin for error. Any mechanical issue or misjudgment during approach could quickly turn catastrophic.

In the photograph, the Cutlass lies broken across the deck, its nose crushed and landing gear collapsed. Flight deck personnel are seen reacting in the aftermath—some rushing to secure the wreckage, others assessing the danger of fire or explosion. The image underscores how vulnerable sailors were during early jet operations, often standing only yards away from aircraft carrying full fuel loads and live ordnance. Every crash posed a serious threat not just to the pilot, but to everyone on deck.

The F7U-3 variant, the most advanced version of the Cutlass, was intended to correct flaws found in earlier models. It featured stronger airframe components and improved avionics, yet many core problems remained. The aircraft suffered from poor visibility during landing, unreliable hydraulic systems, and engines that struggled to deliver consistent thrust. Pilots grimly nicknamed the aircraft the “Ensign Eliminator,” a reference to the number of young naval aviators killed while flying it.

USS Hancock, a veteran Essex-class carrier modernized for jet operations, played a key role in testing and deploying early naval jets during the Cold War. The ship’s deck became a proving ground where new technologies were pushed to their limits. Incidents like the Cutlass crash highlighted the steep learning curve faced by both designers and crews as naval aviation transitioned from propeller-driven aircraft to jets.

Despite its failures, the Cutlass was not entirely without value. Lessons learned from its shortcomings directly influenced later, more successful designs. Engineers gained critical insights into carrier landing dynamics, structural stress, and jet engine integration. Aircraft such as the F-8 Crusader and later naval fighters benefited from the painful experiences associated with the Cutlass program.

The photograph of the crash aboard USS Hancock endures because it captures more than a single accident. It represents an era of experimentation, risk, and sacrifice. Naval aviation advanced rapidly in the 1950s, but that progress came at a heavy human cost. Each wrecked aircraft told a story of ambition colliding with reality, and each accident pushed the Navy to demand safer, more reliable machines.

Today, the Vought F7U-3 Cutlass is remembered less for its intended role as a cutting-edge fighter and more as a cautionary tale. The dramatic image from USS Hancock serves as a stark reminder that innovation without reliability can be deadly. It stands as a tribute to the pilots and deck crews who operated at the edge of technology, often paying the price so future generations of aviators could fly safer skies.